Time Series Decomposition

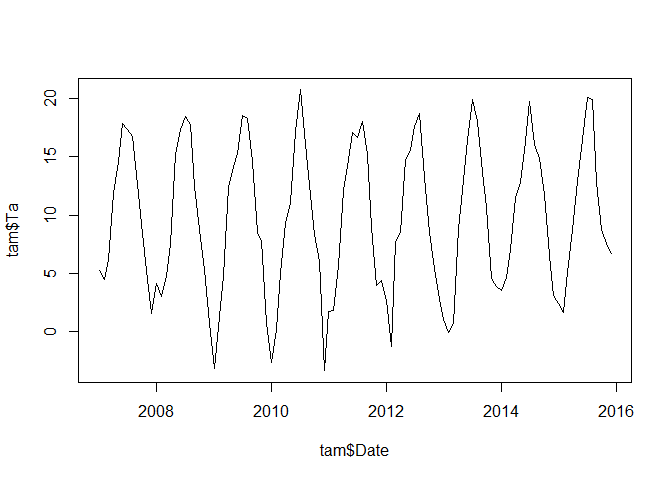

After looking into time-series forecasting, we will now switch to some basics of describing time series. To illustrate this, we will again use the (mean monthly) air temperature record of the weather station in Coelbe (which is closest to the Marburg university forest). The data has been supplied by the German weatherservice German weather service. For simplicity, we will remove the first 6 entries (July to Dezember 2006 to have full years).

tam <- tam[-(1:6),]

tam$Date <- strptime(paste0(tam$Date, "010000"), format = "%Y%m%d%H%M", tz = "UTC")

plot(tam$Date, tam$Ta, type = "l")

Seasonality of the time series

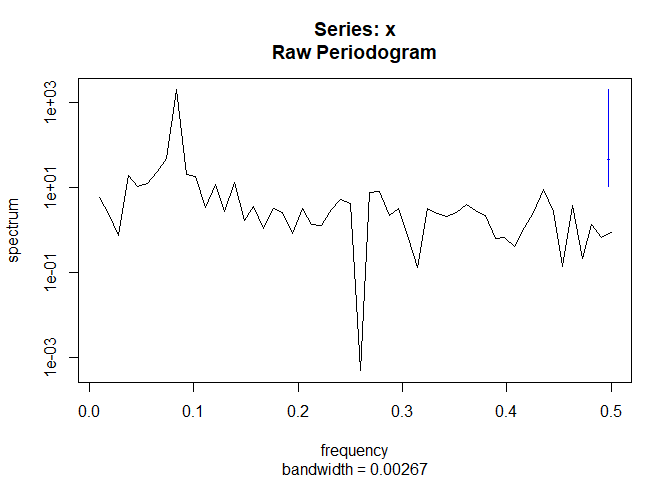

The time series shows a clear seasonality. In this case, we know already that monthly mid-latitude temperature shows a seasonality of 12 month. In case we are not certain, we could also have a look at the spectrum using e.g. the spectrum functions which estimates the (seasonal) frequencies of a data set using an auto-regressive model.

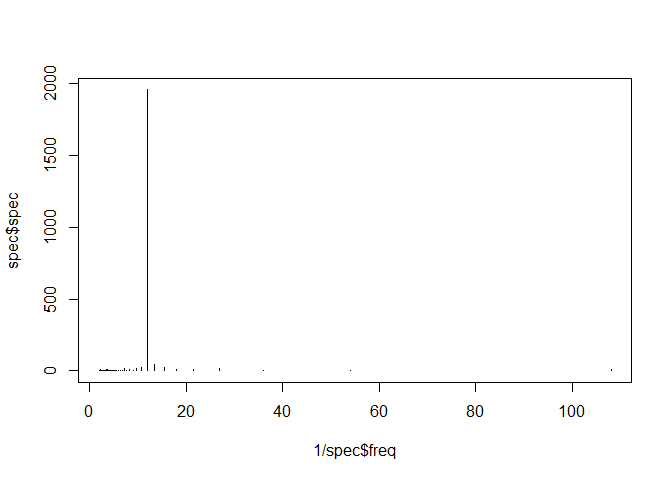

The smalest frequency which is checked is 1 divided by the length of the time series. Hence, in order to convert frequency back to the original time units, we divide 1 by the frequency:

spec <- spectrum(tam$Ta)

plot(1/spec$freq, spec$spec, type = "h")

1/spec$freq[spec$spe == max(spec$spec)]

## [1] 12

The frequency of 12 months dominates the spectral density.

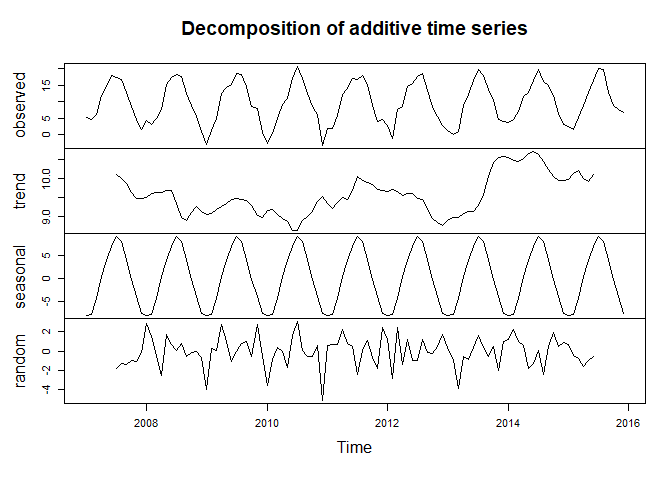

Decomposition of a time series

Once we are certain about the seasonal frequency, we can start with the decomposition of the time series which is assumed to be the sum of

- an annual trend

- a seasonal component

- a non-correlated reminder component (i.e. white noise)

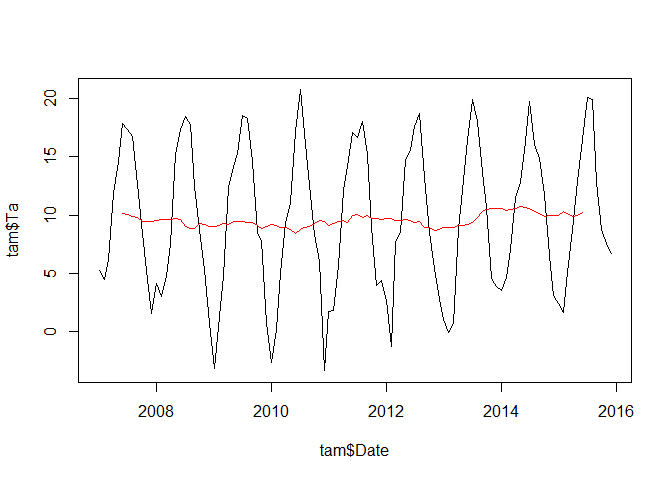

To start with the annual component or “trend”, we could use a 12 month running mean filter. In the following example, we will use the rollapply function for that:

annual_trend <- zoo::rollapply(tam$Ta, 12, mean, align = "center", fill = NA)

plot(tam$Date, tam$Ta, type = "l")

lines(tam$Date, annual_trend, col = "red")

The annual trend shows some fluctuations but it is certainly not very strong or even hardly different from zero.

Once this trend is identified, we can substract it from the original time series in order to get a de-trended seasonal signal which will be averaged in a second step. The average of each will finally form the seasonal signal:

seasonal <- tam$Ta - annual_trend

seasonal_mean <- aggregate(seasonal, by = list(rep(seq(1,12), 9)),

FUN = mean, na.rm = TRUE)

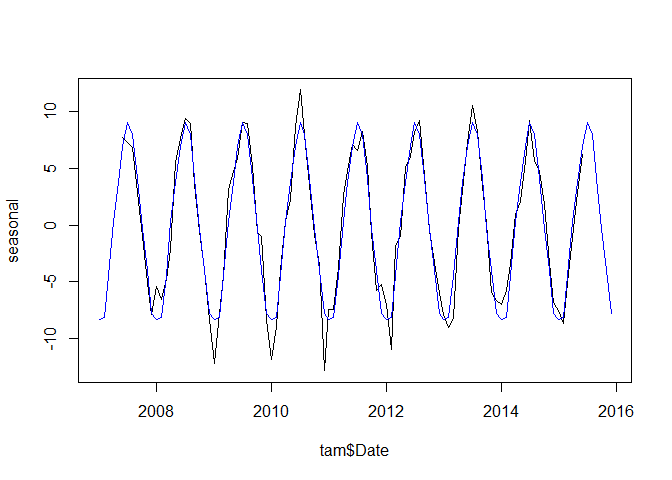

plot(tam$Date, seasonal, type = "l")

lines(tam$Date, rep(seasonal_mean$x, 9), col = "blue")

The blue line shows the average seasonal signal over the time series.

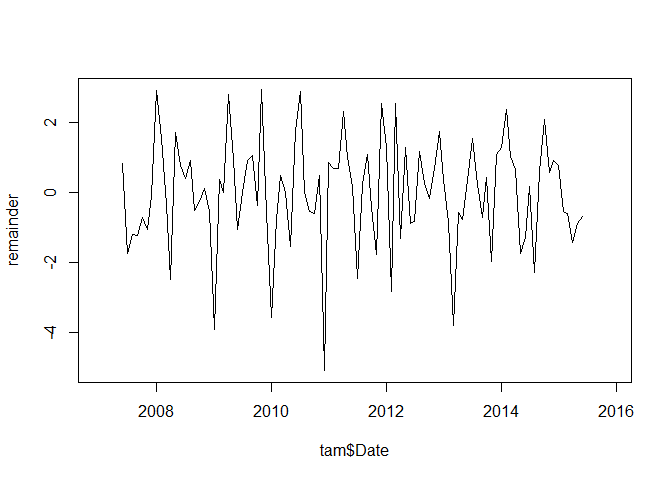

The only thing remaining is the remainder, i.e. the component not explained by neither the trend nor the seasonal signal:

remainder <- tam$Ta - annual_trend - seasonal_mean$x

plot(tam$Date, remainder, type = "l")

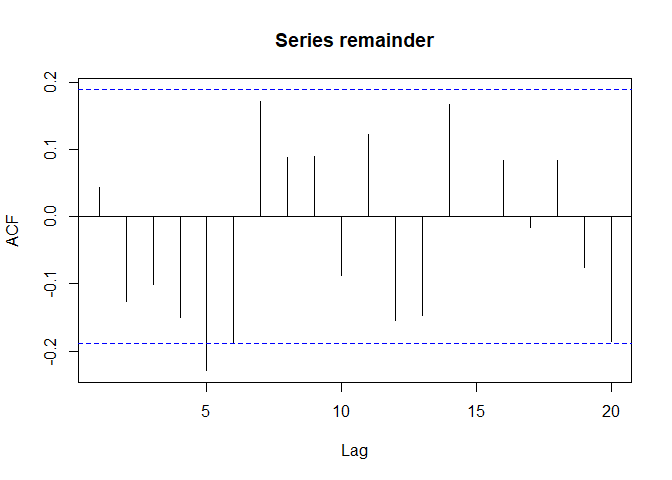

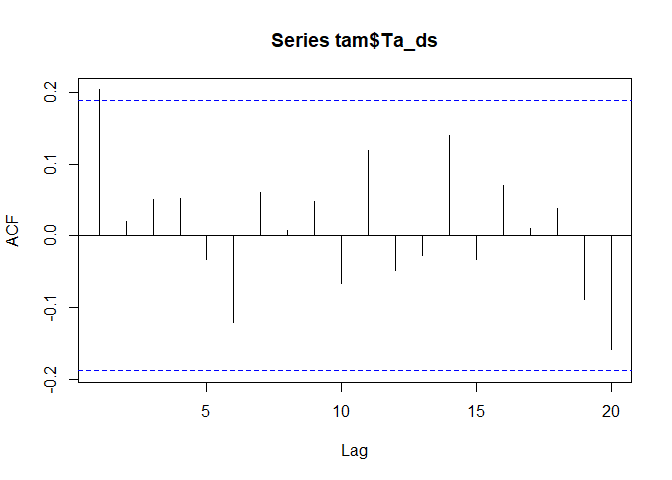

As on can see, it is not auto-correlated:

acf(remainder, na.action = na.pass)

Alternatively to the workflow above, one could (and should) of course use existing functions, like decompose which handles the decomposition in one step. Since the functions requires a time series, this has to be done first. Remeber that the frequency parameter in the time series does not correspond to the seasonal component but to the number of sub-observations whithin each major time step (i.e. monthly values within annual major time steps in our case):

tam_ts <- ts(tam$Ta, start = c(2007, 1), end = c(2015, 12),

frequency = 12)

tam_ts_dec <- decompose(tam_ts)

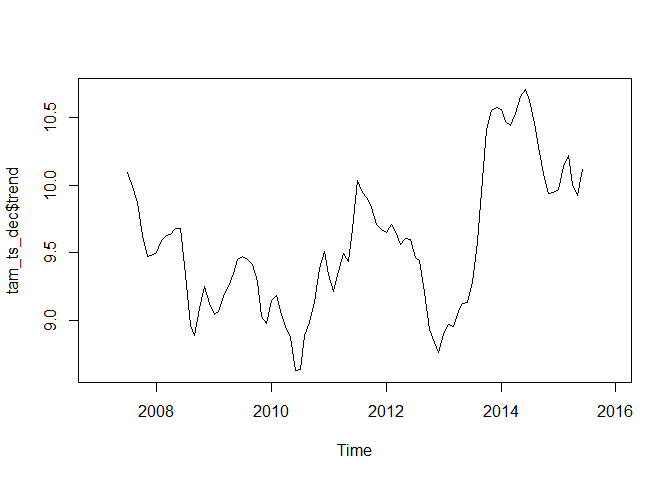

plot(tam_ts_dec$trend)

While the above shows the plotting of the trend component, one can also plot everything in one plot:

plot(tam_ts_dec)

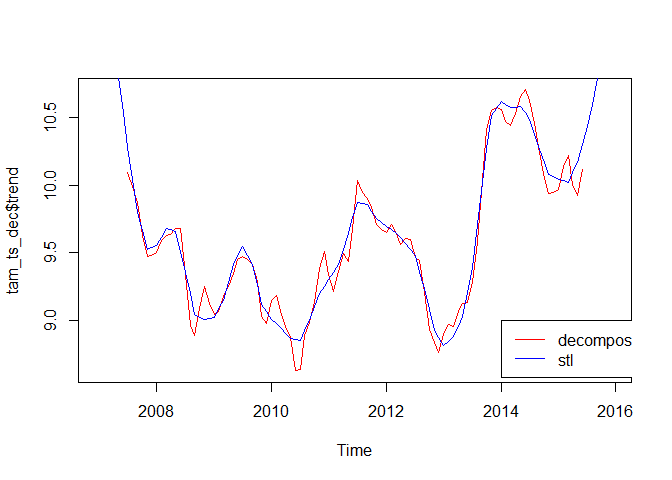

But - again - it is not as static as it seems. While decompose computes the (annual/long-term) trend using a moving average, the stl function uses a loess smoother. Here’s one realisation using “periodic” as the smoothing window, for which - according to the function description - “smoothing is effectively replaced by taking the mean” (the visualization shows the different long-term trends retrieved by the two approaches, there are more tuning parameters):

tam_ts_stl <- stl(tam_ts, "periodic")

plot(tam_ts_dec$trend, col = "red")

lines(tam_ts_stl$time.series[, 2], col = "blue")

legend(2014, 9, c("decompose", "stl"), col = c("red", "blue"), lty=c(1,1))

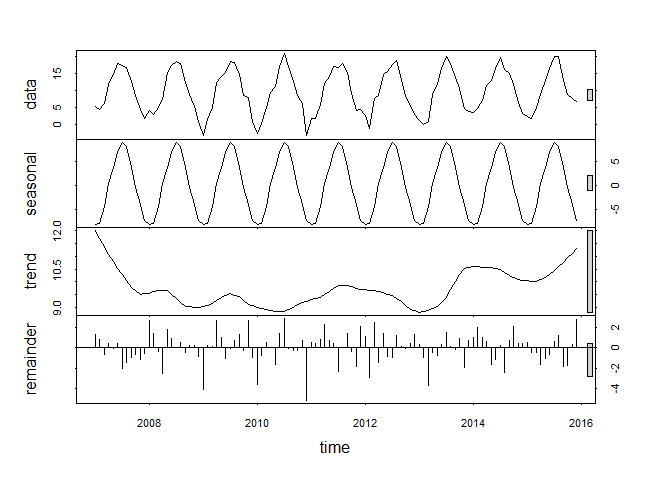

The entire stl result would look like this:

plot(tam_ts_stl)

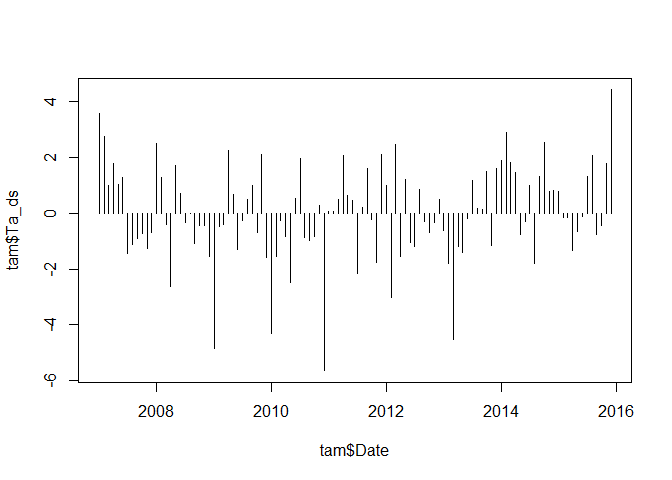

Trend estimation

While the above helps us in decomposing a time series into several components, one is sometimes also interested in some kind of linear trend over time. Since seasonal signals strongly influence such trends, one generally removes the seasonal signal and analysis the anomalies. In order to remove the seasonal signal, one can average over all values for each month and substract it from the original time series:

monthly_mean <- aggregate(tam$Ta, by = list(substr(tam$Date, 6, 7)), FUN = mean)

tam$Ta_ds <- tam$Ta - monthly_mean$x

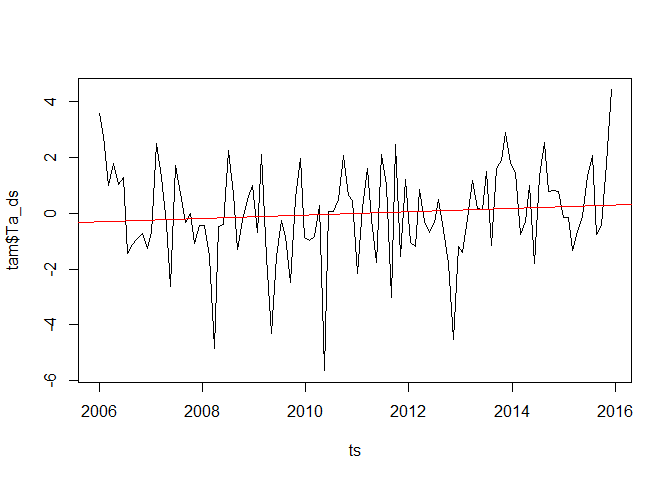

plot(tam$Date, tam$Ta_ds, type = "h")

Once this is done, a linear model could be used. In this context, it is important to understand the meaning of the independent (i.e. time) variable. The following shows the slope of the trend per month since the time is just supplied as a sequence of natural numbers:

lmod <- lm(tam$Ta_ds ~ seq(nrow(tam)))

summary(lmod)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = tam$Ta_ds ~ seq(nrow(tam)))

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -5.6056 -0.9163 -0.1495 1.1346 4.1139

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -0.307379 0.327253 -0.939 0.350

## seq(nrow(tam)) 0.005640 0.005212 1.082 0.282

##

## Residual standard error: 1.689 on 106 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.01093, Adjusted R-squared: 0.001595

## F-statistic: 1.171 on 1 and 106 DF, p-value: 0.2817

If one is interested in annual trends, one can either multiply the above slope of the time variable by 12 or define the time variable in such a manner, that each month is counted as a fraction of 1 (e.g. January 2006 = 2006; Februray 2006 = 2006.0084 etc.):

ts <-seq(2006, 2015+11/12, length = nrow(tam))

lmod <- lm(tam$Ta_ds ~ ts)

summary(lmod)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = tam$Ta_ds ~ ts)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -5.6056 -0.9163 -0.1495 1.1346 4.1139

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -122.37688 113.09365 -1.082 0.282

## ts 0.06086 0.05624 1.082 0.282

##

## Residual standard error: 1.689 on 106 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.01093, Adjusted R-squared: 0.001595

## F-statistic: 1.171 on 1 and 106 DF, p-value: 0.2817

plot(ts, tam$Ta_ds, type = "l")

abline(lmod, col = "red")

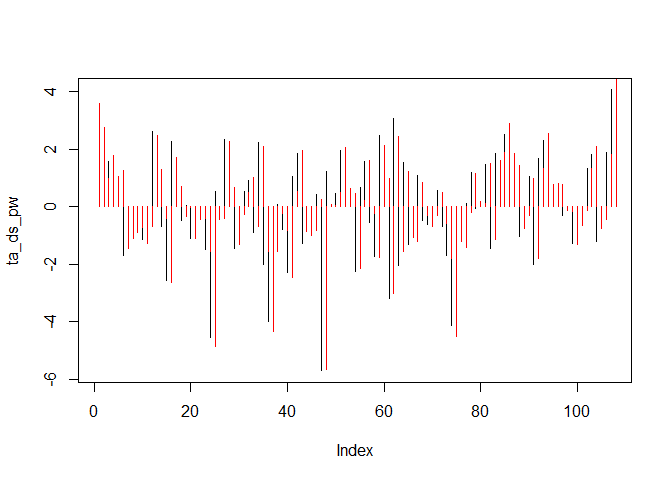

A commonly used alternative or additional information is the Mann-Kendall trend which is a meassure of how often a time series dataset increases/decreases from one time step to the next. If you have a look in the literature, there is quite some discussion if and when the time series should be pre-whitened prior applying a Kendall test. For this example we follow http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-662-03167-4_2 and use a auto-regression based pre-whitening for the time series. The Kendall trend can then be computed e.g. the Kendall::MannKendall function (but also e.g. cor - see the help of this function).

acf_lag_01 <- acf(tam$Ta_ds)$acf[1]

ta_ds_pw <- lapply(seq(2, length(tam$Ta_ds)), function(i){

tam$Ta_ds[i] - acf_lag_01 * tam$Ta_ds[i-1]

})

ta_ds_pw <- unlist(ta_ds_pw)

plot(ta_ds_pw, type = "h")

points(tam$Ta_ds, type = "h", col = "red")

Kendall::MannKendall(ta_ds_pw)

## tau = 0.0898, 2-sided pvalue =0.17146

Kendall::MannKendall(tam$Ta_ds)

## tau = 0.0751, 2-sided pvalue =0.25033