Time Series

Although we already had contact with some temporal datasets, we did not have a closer formal look on time series analysis. Time series datasets often inhibit some kind of autocorrelation, which is a no go for the models we have used so far. The first more formal contact with time series will therefore highlight these characteristics. The structure of this example follows Zuur et al. 2007 to a certain degree.

To exemplarily illustrate a time series analysis, air temperature records of the weather station in Coelbe (which is closest to the Marburg university forest) will be used. The data has been supplied by the German Weather Service.

A first look at the time series

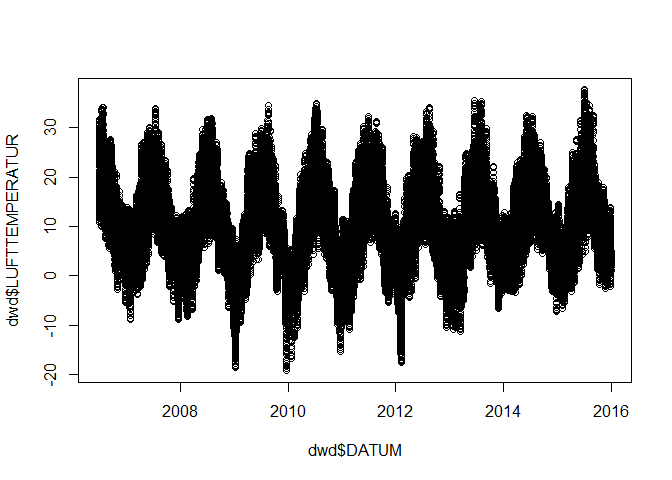

The time series shows hourly recordings of 2m air temperature between July 1st 2006 and December 31st 2015.

head(dwd)

## STATIONS_ID MESS_DATUM QUALITAETS_NIVEAU STRUKTUR_VERSION LUFTTEMPERATUR

## 1 3164 2006070100 3 38 12.9

## 2 3164 2006070101 7 38 12.1

## 3 3164 2006070102 7 38 11.8

## 4 3164 2006070103 7 38 11.6

## 5 3164 2006070104 7 38 11.7

## 6 3164 2006070105 7 38 13.2

## REL_FEUCHTE eor

## 1 91 eor

## 2 91 eor

## 3 93 eor

## 4 90 eor

## 5 91 eor

## 6 86 eor

tail(dwd)

## STATIONS_ID MESS_DATUM QUALITAETS_NIVEAU STRUKTUR_VERSION

## 83297 3164 2015123118 7 38

## 83298 3164 2015123119 7 38

## 83299 3164 2015123120 7 38

## 83300 3164 2015123121 7 38

## 83301 3164 2015123122 7 38

## 83302 3164 2015123123 7 38

## LUFTTEMPERATUR REL_FEUCHTE eor

## 83297 4.5 98 eor

## 83298 4.3 100 eor

## 83299 4.3 100 eor

## 83300 4.3 100 eor

## 83301 4.4 100 eor

## 83302 4.5 99 eor

In order to plot the dataset in a correct manner (i.e. without large gaps at the end of the year when e.g. 2006123123 switches to 2007010100), the data can either be tranformed to a timeseries ts object or the date column can be converted to some kind of date format.

Since we will have a closer look on ts objects later, let us start with the date conversion.

For this purpose, it is necessary to additionally provide minutes to the given date/hour information.

dwd$DATUM <- strptime(paste0(dwd$MESS_DATUM, "00"), format = "%Y%m%d%H%M")

head(dwd$DATUM)

## [1] "2006-07-01 00:00:00 CEST" "2006-07-01 01:00:00 CEST"

## [3] "2006-07-01 02:00:00 CEST" "2006-07-01 03:00:00 CEST"

## [5] "2006-07-01 04:00:00 CEST" "2006-07-01 05:00:00 CEST"

Plotting is now easy:

plot(dwd$DATUM, dwd$LUFTTEMPERATUR)

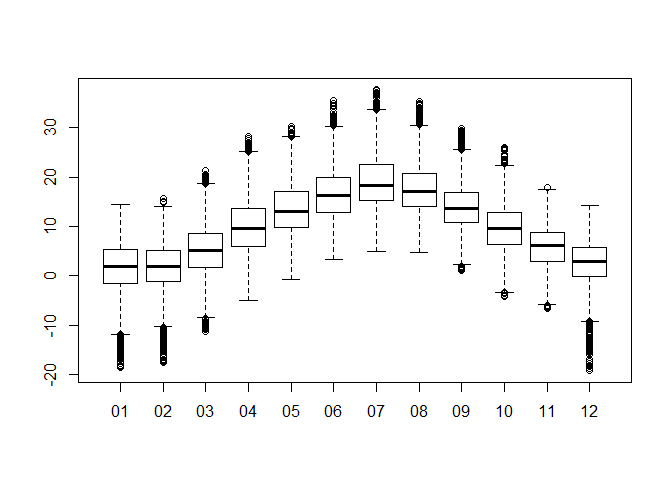

As one can see, there is a clear annual pattern (surprise, surprise). To have a closer look on this pattern, one simple option would be a set of boxplots showing the variation within each month over the entire dataset. To do so, the data in the boxplot has to be grouped by months, what requires a list indicating the class (i.e. month) each temperature record belongs to. The easiest way is to create an additional column in the data frame and copy the characters which define the month in the original date column to it.

dwd$AGG_M <- substr(dwd$MESS_DATUM, 5, 6)

boxplot(dwd$LUFTTEMPERATUR ~ dwd$AGG_M)

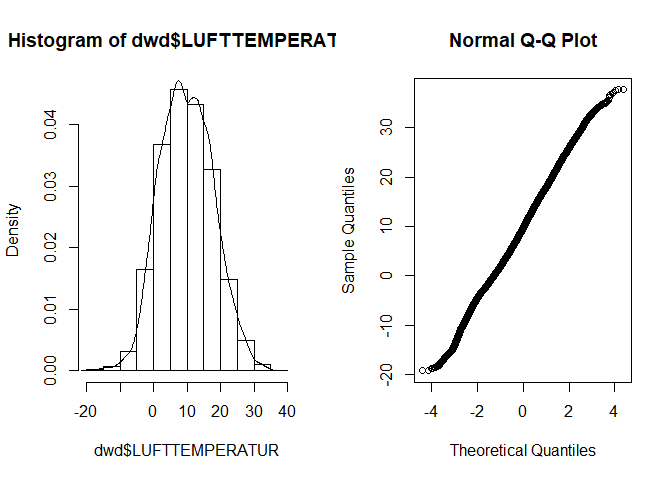

If you wonder about the distribution, you can use what we learned so far:

par_org <- par()

par(mfrow = c(1,2))

hist(dwd$LUFTTEMPERATUR, prob = TRUE)

lines(density(dwd$LUFTTEMPERATUR))

qqnorm(dwd$LUFTTEMPERATUR)

par(par_org)

Auto-correlation

So far, we always assumed that different observations are independent of each other - a concept which cannot be hold for many time series. Understanding auto-correlation is rather easy. It is the Pearson correlation we already know but not computed based on two different datasets/variables but computed using the same time-series dataset with a temporal lag. For example, the auto-correlation for a lag of 1 would compare each original value observed at time t with the observed value at time t+1. A lag of 10 indicates that observation at time t is correlated with observation t+10 and so on. Please note that the number of available data pairs decreases (e.g. if the dataset has 30 observations, one has 29 pairs for lag 1 but only 1 pair for lag 30). Therefore, it does not make sense to try any possible lag but restrict it to a few lags or to lags which one expext to be highly correlated (e.g. lag 12 for the monthly temperatures above).

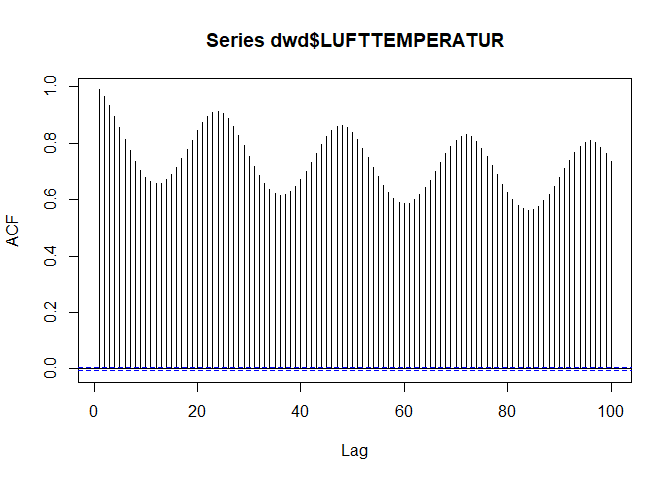

While one can have a look at the actual correlation values, a visualization generally gives a better overview:

acf(dwd$LUFTTEMPERATUR, lag.max = 100)

Since we have more than 80.000 values available, we can use a maximum lag of 100 although this is done mainly for illustration purposes. Obviously, we have strongest correlations at lags of 24 (i.e the correlation between hourly temperatures is highest if the temperatures are meassured at the sime time of day). While this holds true, the absolute correlation decreases if the number of days between the observations increases.

Another example shows the auto-correlation of the monthly mean temperatures for which we define an aggregation variable like the one above but this time we include not only the month but also the year:

dwd$AGG_JM <- substr(dwd$MESS_DATUM, 1, 6)

tam <- aggregate(dwd$LUFTTEMPERATUR, by = list(dwd$AGG_JM), FUN = mean)

colnames(tam) <- c("Date", "Ta")

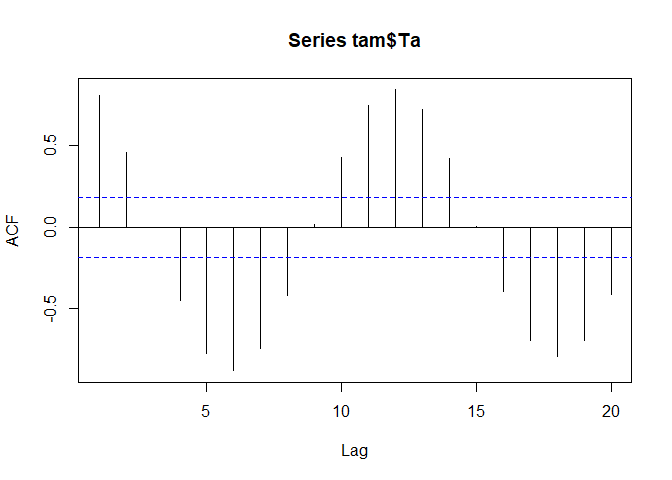

acf(tam$Ta)

Now the seasonal pattern becomes evident with negative correlations with a lag of around 6 months (summer/winter, spring/autumn) and positive correlations with lags around 12 month. The blue lines indicate the significance corresponding to a p value of 0.05 if normality can be assumed. The latter is generally the case for time series longer than 30 to 40 values for which the central limit theorem becomes effective.

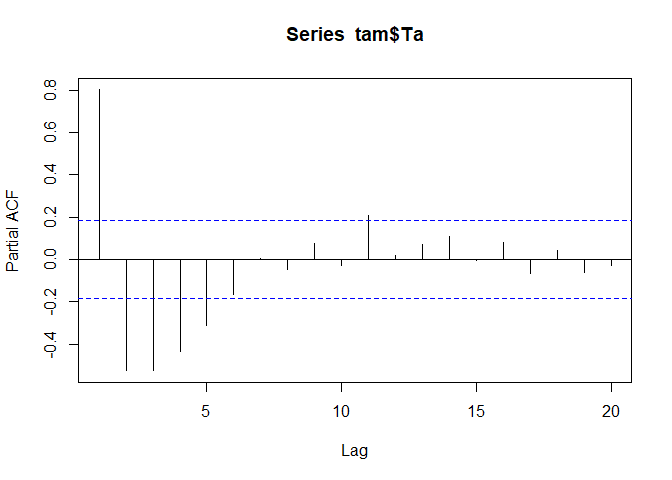

Aside from the auto-correlation, we could also look at the partial auto-correlation. The difference between those is that in the partial auto-correlation, the correlation between time lag t=0 and e.g. time lag t=t+10 is computed in such a manner that the influence of the auto-correlations in between is eliminated. This leads to quite different results. For example, if you have a strong auto-correlation with lag 5, than it is not surprising that t=0 is not only related to t=t+5 but also to t=t+5+5. The partial auto-correlation of our dataset looks like this:

pacf(tam$Ta)

One can also use test statistics like a Box-Pierce or Ljung-Box test:

Box.test(tam$Ta, lag = 10, type = "Box-Pierce")

##

## Box-Pierce test

##

## data: tam$Ta

## X-squared = 378.96, df = 10, p-value < 2.2e-16

Box.test(tam$Ta, lag = 10, type = "Ljung-Box")

##

## Box-Ljung test

##

## data: tam$Ta

## X-squared = 403.41, df = 10, p-value < 2.2e-16

Both tests add up the correlation coefficients until the given lag and compare them to a theoretical distribution.

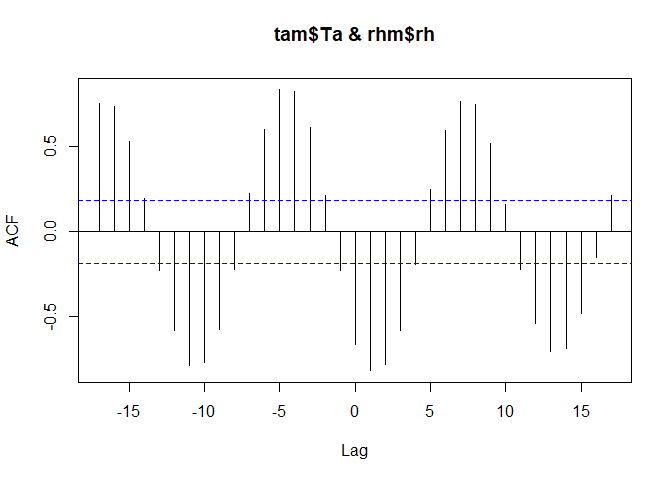

Of course, one can also have a look at cross-correlations including time lags. As example, we use relative humidity which is also part of the dataset.

rhm <- aggregate(dwd$REL_FEUCHTE, by = list(dwd$AGG_JM), FUN = mean)

colnames(rhm) <- c("Date", "rh")

ccf(tam$Ta, rhm$rh)

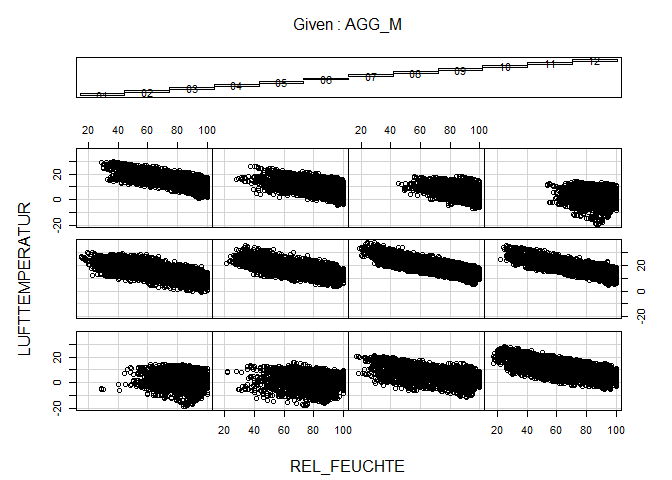

Similar. Air humidity is auto-correlated to air temperature. And this relationship is pretty much the same over all months (as you can find out if you still remember a plot type from the very beginning of this course):

coplot(LUFTTEMPERATUR ~ REL_FEUCHTE | AGG_M, data = dwd)

Auto-correlation analysis gives also a hint on stationarity. Stationarity is essential if one e.g. wants to predict future time series values based on auto-regressive or moving average models. Stationarity means that the time series has no trend and has similar variance over the entire time span. This is clearly not the case in the temperature data because of the strong seasonality regardless of any long term trend.